A Eulogy

for Thomas Edward DeFreitas, Sr.

6 July 1940 -- 2 March 2018

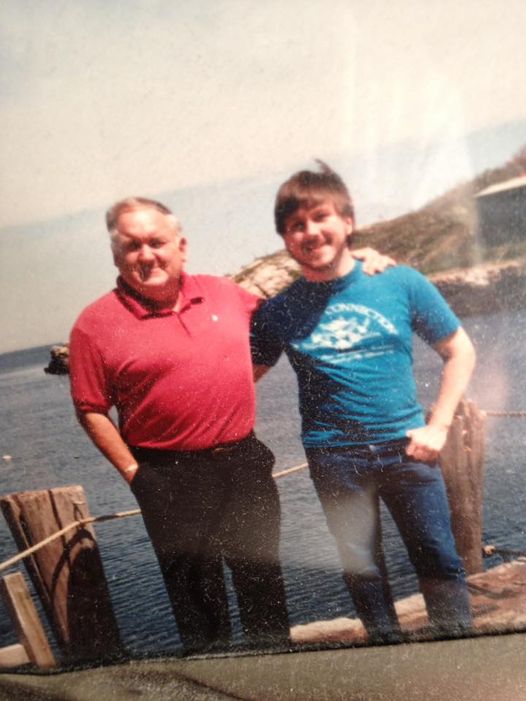

Good afternoon, and thank you all for being here to pay final respects to Thomas Edward DeFreitas, Big Tom, Tom the Bomb, Mai Tai Tom, your brother, your uncle, your husband, your relative, loved one, buddy, pal, friend—my dad.

Memories! When I was about 14 years old, and sulking over some routine adolescent setback, Dad thumbtacked a clipping from The Boston Sunday Globe onto my bedroom door. It was a quotation from President Theodore Roosevelt:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; […] who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly.

Dad was always one who dared greatly. He didn’t shrink from a challenge. He didn’t draw back from any new adventure, whether it was joining the Marines with Uncle John, going whitewater rafting with Bartolo Club buddies, or leading me and the Crowley kids on a hunt for the ever-elusive snipe. Dad lived with gusto. He enjoyed life. He was one who could say with the Irish poet James Stephens:

Let us go out and walk upon the road

And quit for ever more the brick-built den,

And lock, and key, the hidden shy abode

That separates us from our fellow men.

Dad wasn’t much for anything hidden, shy, or separate. Dad went out and walked upon the road. Walked? Come to think of it, he actually drove upon the road, and got more than his share of speeding tickets in so doing! He liked a good drive in the White Mountains in his beloved New Hampshire. He liked a good meal, a good drink, a good story, a good joke, a good game. He relished vigorous competition: track meets in his teens, baseball and football in his 20s, tennis in his 30s, golf in his 40s and beyond. In his prime, he was an able-bodied athlete, a jovial raconteur, a feisty humorist. As a father, he was a steadying hand who knew both how to encourage and how to draw boundaries.

On those occasions when I got too full of myself, too much of a swelled head, Dad would provide the pin that punctured the hot-air balloon. Think Marty Crane in “Frasier.” With a bit of a Tom DeFreitas edge! Whenever I did something especially clueless or dimwitted or dopey, Dad would lovingly say, in a gentle voice, “If you had two brains, one of them would die of loneliness!”

But I don’t want to give the wrong impression. He always had my back. When I lost the sixth-grade citywide spelling bee, and was literally sobbing with disappointment, he gave me a pep talk, and took me out for a hearty, hefty lunch (one of many hearty, hefty DeFreitas family lunches!). When I needed a chauffeur to the senior prom, I had to look no further than Dad and his handsomely appointed ’79 Cadillac. When I was in hospital in my 20s, he came every week without fail to give me the two things I most looked forward to: a copy of the latest Newsweek and a large vanilla frappe. In my 30s, when I was living in Chelsea, we went out once a week for breakfast at Savino’s Diner. He bought me a kitchen table from Bernie & Phyl’s when I moved to Arlington at age 40. And though he must have been mystified by the twist of fate or quirk of divine whimsy that gave him a poet for a son, he was always glad to hear about my writing, my workshops, and my efforts at getting published. He was a valued counsellor when I was uncertain, a sturdy bulwark when I was fretful, a clear-headed sage when I was in doubt.

Dad was a man of many enthusiasms (New Hampshire, golf, fall foliage, my late grandmother’s eggplant), but he also harbored a few intractable dislikes:

Seafood. Dad thought there was something fishy about seafood. He didn’t trust the Gorton’s fisherman.

Dad didn’t much care for the golfer Gary Player. Gary Player was the winner of the 1965 US Open. Mr. Player would never take off his hat to acknowledge the applause of a crowd, but would merely tug at the brim a little, while leaving the hat firmly fixed on his head. This drove Dad batty! “If you’re going to tip your hat to the crowd, take the flippin’ thing off your head!”

And Dad had little use for the word “potential.” More than once, he said that “potential” was the weakest word in the English language. Dad liked people who converted their potential into purposeful effort, into visible movement toward a fixed and worthy goal. Like Theodore Roosevelt, he admired more the one who tried and failed—maybe fell flat on his face a thousand times over before he succeeded—but he withheld his respect from the one who never tried in the first place—who played it safe, buried his talent, stood on the sidelines. And in Dad’s world, when you fell down (and you would fall down!), you dusted yourself off, and got right the heck back up!

Dad’s fighting spirit was very much in evidence during his last months, as he contended against weakened heart and failing kidneys, plagued by frequent bleeding, nettled by the litany of woes, ills, complaints, and “the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to.” During this time, his good friend Evelyn Morris was tireless in her exertions on Dad’s behalf. Dad benefited mightily from the skill and solicitude of the doctors, nurses, and other health care providers at Rosewood Rehab, at Salem Hospital, and with Care Dimensions. One doctor at Salem, Dr. Coleen Reid in Palliative Care, distinguished herself by being particularly attentive and compassionate toward Dad and toward those of us closest to him. Dad always welcomed visits from Uncle Bob, Uncle Bill, and Uncle Clark. He keenly appreciated their boisterous good humour and quietly rejoiced in their brotherly love. In recent days, it was a profound consolation that Mom and my friend Heather and I were able to spend four hours with Dad at Rosewood the night before he died: to hold his hand; to speak to him, confident that he could sense our presence; to pray as Fr. MacInnis anointed him; and to watch as Dad consumed his last strawberry Popsicle.

In 1951, my favourite poet, Dylan Thomas, wrote to his dying father to urge him to battle back against his infirmities and not to give in. Some of you may be familiar with the poet’s ringing words:

Do not go gentle into that good night;

Old age should burn and rave at close of day.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

But there comes a time when, in the words of the late New Hampshire poet Jane Kenyon, we must “let evening come.” Kenyon’s famous poem urges:

Let it come, as it will, and don’t

be afraid. God does not leave us

comfortless, so let evening come.

Evening came for Thomas Edward DeFreitas on a cold, rainy Friday, March 2, 2018 at the age of 77. Faith tells us that he now has been taken up to a place of perpetual light and everlasting refreshment. A place of communion with God and with God’s faithful; a place of reunion with his parents (my grandparents) Thomas and Clementine, with Aunt Lou and Uncle T, with Uncle John, with Aunt Maureen. A place where it is never “that good night,” but always the glorious dawn of a brand new day. Dad wondered when this winter would end; now he has found his eternal spring. He can now say, as St Paul did in his second letter to Timothy: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith.”